BLOG

Please note that this blog was created in 2004. Although the world has undergone enormous transformations since the landmark event of September 11, 2001 in the United States, which ushered in a new era focused on global security, other key events have also had a major impact and continue to shape the recent history of the 21st century. These include the 2008 market crisis, the mass adoption of mobile phones, the development of wireless networks and the rise of social platforms, the Fukushima disaster, the emergence of Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies, as well as the controversial COVID-19 pandemic, mass migration, AI and the creation of the BRICS, to name a few.Pierre Duranleau - 2024

Duisburg-Nord: Laboratory or Park?

Introduction

Between 1870 and 1920, a cluster of small towns established a major industrial and residential zone along the banks of the Ruhr in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. 1Spanning an area of approximately 140 km, this region represents an archetype—dotted with structures and blast furnaces that resemble industrial cathedrals—that embodies the zeitgeist of the Industrial Revolution in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century and, more specifically, would play a crucial role in the German economy. A region that stands out as one of the most significant in this industrial corridor is Duisburg-Nord (with a population of around 2.5 million), and in particular, the Duisburg-Meiderich steel plant, where the coal mines of the Thyssen company produced over 37 million tons of steel between 1900 and 1985. 2Industrial production reigned in this region, becoming the economic engine of the area for nearly a century. Notably, there was a lack of public recreational parks (i.e., the Volkspark) during this long period of stability and prosperity. However, as was the case in the West and much of the industrialized world in the early 1980s, there was a systematic closure of factories tied to the oldest industrial economic sectors; Duisburg-Nord was not immune to this transformative wave. Due to these events, the region’s economy shifted towards a service-based economy. A large number of industrial facilities in this region were abandoned, creating a new aesthetic of ruins—artifacts and remnants of the industrial era.

Blast Furnaces - Duisburg-Nord

1 - Leppert, p.34.

2 - Weilacher, p.122.

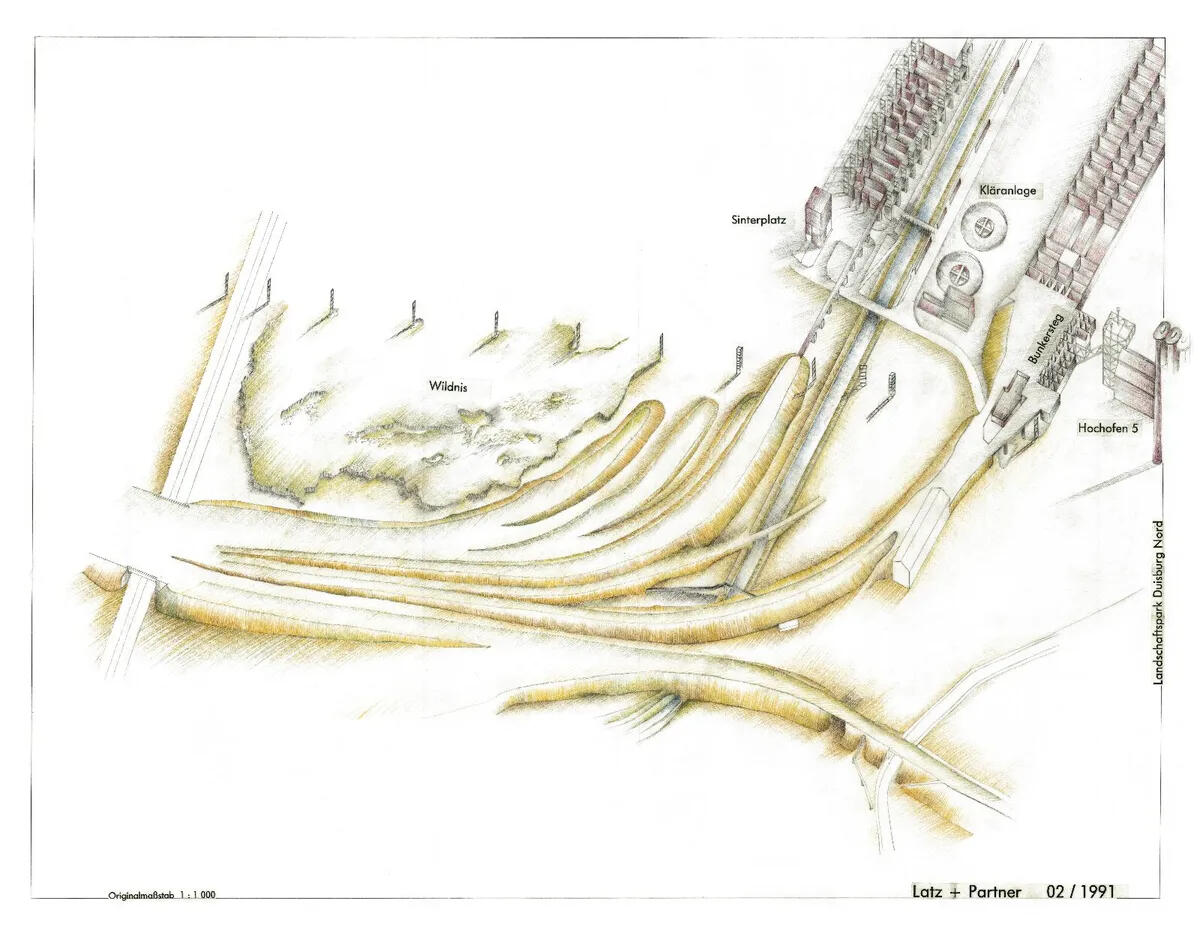

Introduction of the IBA: International Bauausstellung (International Building and Urban Development Exhibition Emscher Park).A corporation formed in 1989, with its sole shareholder being the province of North Rhine-Westphalia. The initiative and mission: to rehabilitate the Ruhr Valley - an environment marked by polluting industrial activity—from the perspective of sustainable development. This involves renaturalizing the landscape, revitalizing the region’s economic, ecological, social, and cultural activities, and giving the region a new identity. The IBA launched its first project, which involved the establishment of a public park on the site of a former metallurgical plant in Duisburg-Nord. The first prize for this project was awarded to the firm Latz & Partner 3, with the project being realized between 1990 and 1999. 4

Context

Post-Modernism

Towards the end of the 20th century: a term referring to an amorphous body of cultural trends and movements, marked by eclecticism, multiculturalism, and an internationalist high-tech framework of reference. This was paradoxically paired with a skeptical critique of the same technological progress that had given rise to this phenomenon. 5

Post-Industrial Society

Economically, since the 1980s, characterized by a shift from goods production to a service-based economy; the preeminence of professional and technological classes; the creation of a new intellectual technology (high-tech) and its derivative, intellectual property. There have been increasingly vast socio-economic divides between the most advantaged countries and those still developing. The darling of the NASDAQ stock exchange: the arrival of the dot-coms. This period is generally associated with excess, cynicism, and individualism, which are unmistakable marks of this new iteration of capitalism.

The Harp or Rails - Duisburg-Nord

3 -For more information (biographical, etc.) concerning Latz & Partner, follow the link below:

4 - Brandolini, p.75.

5 - Bullock et Trombley, p.673.

New Media and New Technologies

Since the late 1980s, there has been a dizzying evolution in research and development of new technologies: communications, computing, cybernetics, and bio-genetics. Neuromancer, the imagination of William Gibson and its new virtual space, Cyberspace, along with Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner, gave birth to the Cyberpunk movement; the birth of the internet; the proliferation of digi-cams and cell phones; the spread and democratization of digital technology; the plug and play culture.

"William Gibson, by publishing Neuromancer, will forever be credited with having created the word 'Cyberspace.' This cyberpunk novel, coincidentally released in 1984, partly echoes George Orwell’s famous work. Harsh and dystopian, cyberspace first appears as a place of consensual hallucination, marked by extreme violence and capitalism pushed to its limits. But cyberspace also incorporates the vision of a collective consciousness, a brain of brains, so to speak, a new horizon for humanity, reconstituted in a different way…" 6

W. Gibson's novel Neuromancer

6 - Guédon, p.92-93.

Global Village

In contrast to McLuhan’s original and utopian vision, today’s Global Village is marked by the alarming decline of cultural diversity; technology fosters closer ties between societies, but in doing so, it also leads to cultural sterility and homogeneity (the melting pot effect).

Space Exploration

An inevitable shortage of resources and habitable space, coupled with the eventual degradation of the biosphere, will push humanity toward its ultimate destiny: the colonization of space in the 21st century. Since the 1970s, we have already begun the process of studying and exploring the planet Mars in the hope of finding signs of life and developing strategies and technologies to make this world habitable through terraforming: a monumental-scale landscaping intervention on a planetary level. This will require unprecedented mastery of ecological and technological systems to create a fourth nature.

"What I find most fascinating are systems which, on the one hand, have to meet extremely high technical standards and, on the other hand, develop virtually ideal ecological qualities. The components of these systems are so closely linked that the ecological aspect disappears if the technology fails, and the technology disappears if the ecology no longer works. We need to understand that this is how much of the world functions. What nature conservationists fought against thirty years ago as an extreme form of environmental destruction is now protected by law." 7

Piazza Metallica - Duisburg-Nord

7 - Weilacher, p.130.

Duisburg-Nord :

Intention, Philosophy and Syntax

If John Dixon Hunt refers to the garden as a third nature 8, can we define the transformation of the post-industrial site of Duisburg-Nord into a public park as a fourth nature transformation? The original natural/cultural landscape gave way to industry; the latter created a new form of landscape, known as technological. This landscape, polluted, scarred, and disrupted, is once again modified and restored through an opportunistic, adaptive, and intuitive vision of landscape intervention.Before the Duisburg-Nord project, Peter Latz was already contemplating the notion of eliminating the separation between nature and culture; never could he have imagined that this contemplation would manifest in a post-industrial landscape. 9 In 1985, Latz was awarded a significant contract for the rehabilitation of a former industrial site: the coal port in Saarbrücken. Latz & Partner transformed this site in the manner of a Roman ruin, using as motifs architectural elements (both existing and new), with pedestrian paths overrun by opportunistic plant species. The Saarbrücken experience became both the pilot project for Duisburg-Nord and Peter Latz's aesthetic signature: the fusion of ecological thought with an enthusiasm for technological entropy. 10

8 - Greater perfections, J. D. Hunt, p.62.

9 - Metropolis, p.128.

10 - Ibid.

Latz’s vision invites a new way of considering the urban environment; nature and industry are seen as two distinct ecological systems, giving rise to an aesthetic of conservation, infrastructure organization (system building), reappropriation, recycling, and a more refined awareness of design and intervention processes. In short, an aesthetic, primarily of sustainable development. 11 In the case of Duisburg-Nord, the central idea lies in the restoration and preservation of the genius loci, creating a favorable situation for a new organization of the site based on rational and structured approaches, with an emphasis on experimentation and opportunistic exploitation of the environment.

”The seemingly chance results of human interference, which are generally judged to be negative, also have immensely exciting positive aspects, are, on closer inspection, ultimately even a contribution of nature conservation. These sites offer potential for the development of things which are completely different." 12

The traditional notion of a park is thus challenged in the case of the Duisburg-Nord project. At first glance, it is an intervention—on a larger scale—where the space undergoes transformations evoking motifs characteristic of the Land Art movement. The presence on-site of slag heaps, from which wild plants grow, suggests certain aesthetic properties present in the work of Robert Smithson, such as his Asphalt Rundown intervention (1969) . In Smithson's work, the environment is disrupted by human intervention using synthetic materials; in contrast, Latz integrates existing human-made elements into the site, perceived as artifacts worthy of the region's industrial heritage, giving them new interpretation and meaning. Aside from the idea of a park perceived as an artistic landscape work, the site also takes on the role of a true laboratory, allowing for experimentation between nature and technology. Consider the Secret Garden, arranged in the former coal and iron ore bunkers, which defines a new formal and functional approach, introducing a garden or park with phyto-restorative potential.

« I can imagine a garden bed which is entirely made up of a substrate of rusty screws.” 13; “The most natural system in the sense of the ecology, is at the same time the most important managed technical system. And that’s the idea of this postindustrial landscape.” - Peter Latz 14

Asphalt Rundown: Robert Smithson (1969)

Here, nature and technology intersect in this park, giving rise to new meanings and archetypes. While it is essential to resist the temptation to interpret Duisburg-Nord in terms of romantic mythology, it is difficult to entirely escape it. The presence of immense industrial structures, such as blast furnaces erected in the topology of a valley, can be perceived as symbolic mountains punctuating the landscape, almost like a real mountain range.

"When you start looking at the blast furnace as a mountain, all these archetypes start coming up. The furnace is not just a blast furnace, it’s a mountain. And, at the same time, it’s a dragon.”

- Peter Latz 15

Hochofenpark - Duisburg-Nord

11 - Metropolis, p.167.

12 - Weilacher, p.129

13 - Ibid, p.130.

14 - Steinglass, p.128.

15 - Ibid

Program et Analysis

The approach envisioned for Duisburg-Nord is not an attempt to deny the site's fragments and discontinuities but seeks a new interpretation of existing structures. Four fundamental and distinct layers characterize the space: the water park, with its canals and reservoirs; the main promenades; the Bahnpark (railway) and the elevated walkways. These elements were to remain autonomous yet visually, functionally, spiritually, and symbolically linked in certain specific places through the introduction of physical links serving as interfaces: stairs, railings, terraces, and gardens. 16 The intention is to create a syntactic concept to ensure the site's optimal future flexibility. In a way, the concept developed by Latz and his team cannot be considered a finished plan. 17 One could even suggest that the park (and the site in general) is in a state of incompletion; in other words, a constantly evolving work in progress.

The location of Duisburg-Nord is in the Emscher Valley, a territory transformed and marked by a network of complex and varied infrastructures: a highway transport network winding among viaduct structures, ramps, and underground passages; an active railway network (the harp of rails), while other tracks have been converted into pedestrian paths; and a network of gas and chemical transport pipelines. All these elements, combined with industrial artifacts and architecture, intertwine to form a rich and complex fabric, serving as a framework for the key elements of the park. 18

The most important area, in terms of interest and activity concentration, is at the center of the site, at the intersection of the Emscher Canal and the circulation network (e.g., the harp of rails, elevated pedestrian paths, and the labyrinth of ore bunkers). This central part and the peripheral area form a triangular configuration where the landmarks, attractions, and most striking elements of the park are located.

The spatial interpretation of the park somewhat defies a conventional reading, in that the viewer is not forced to adhere to a predefined circulation plan. Although there is a circulation and promenade system in place that guides the public to specific destinations on the site, including the harp of rails that directs the viewer to the labyrinth of ore bunkers, and the elevated promenades that lead the observer to the blast furnace park, the appreciation and interpretation of the landscape of Duisburg-nord follows a programming formula that is in keeping with the spirit of an individualistic post-industrial society. In other words, the social, psychological and physical experience of the park is lived according to the individual’s interpretation, in a spontaneous and random way, and in this regard there has been a significant change in the program and use of the park since the beginning of the last century. Today, the idea of a park designed for all is being questioned:

“The people’s park is history. It had a clear program that evolved from social relations in the twenties. In those days people would go to the park together” - Peter latz 19

Sinter Park Gardens (Secret gardens) - Duisburg-Nord

16 - Weilacher, p.124.

17 - Ibid.

18 - Brandolini, p.77.

19 - Diedrich, p.34.

Cultural Elements

The Gasometer : A cylindrical structure approximately 100 meters high, once a gas reservoir, has been transformed into an industrial exhibition center. In addition to its cultural role, visitors can ascend to the top (via elevator) for a panoramic view of the industrial landscape. Its shape recalls the belvedere motif in Romantic gardens.

Piazza Metallica : A dominant icon of the park, recognizable by the 49 steel slabs (at ground level) installed among the remnants of the former manganese foundry. This space serves as a crossroads and gathering point for festivals, performances, 20 and other events, and its form evokes the traditional piazzas, such as Piazza San Marco in Venice.

Artist installations: Note the work of the American sculptor Richard Serra, Halde Shurenbach. Located in Essen on the outskirts of the park, in a place that could only be described as an apocalyptic scene, due to the immense coke mounds and the presence of craters completely devoid of vegetation, this installation is not accessible by road and the pilgrimage is on foot. 21 Another major attraction is the work of the British artist Jonathan Park, whose Theatre of light; the installations of the blast furnace park undergo a singular transformation during the night, by a light show projecting a pattern of colours on all the built and plant surfaces of this location. 22

Industrial Historical Museum: The Duisburg-Nord region is considered a significant industrial heritage in Germany. In this respect, the physical presence of the factories and industrial installations on the site suggest the character of a living historical and cultural museum, and the public is invited to participate in the guided tours offered by the park organizers, where one can visit, among other things, functional factories.23

20 - Diedrich, p.30-31.

21 - Brandolini, p.147.

22 - For more details détails, consult the following resource for Landschaftspark-Duisburg-nord :

23 - Ibid.

Recreational Elements

Although the park as a whole offers a variety of pleasant places for various spontaneous recreational activities, three installations can be highlighted that symbolize the intelligent adaptive appropriation aspect of the spaces and rubble of the site:

Diving Club: A diving club practices their sport in the old gas tanks, which were cleaned and filled with water, thus transforming them into diving training pools 24;

Alpine Club: The members of an alpine club, for their part, enjoy an unparalleled facility located in the old iron ore bunkers, known as the “alpine climbers’ garden”. The climbers exploit to their advantage the accidental elements of the site used as crampons, including the crevasses and faults dug into the walls and the concrete towers that make up the bunker space 25;

Children's Playground: Also located in the structure of the holds, children can have fun in an environment designed from machines converted into a play area where we find, among other things, a slide in the shape of industrial piping; a dream environment for children where abandoned industrial remains stimulate the imagination and discovery. 26

Alpinists - Duisburg-Nord

24 - Leppert, p.37.

25 - Kirkwood, p.152.

26 - Op cit.

Gardens and Ecological Elements

One of the fundamental layers of the park is undoubtedly the ecological system, which refers to the plant and aquatic components arranged throughout the site. We discover an amalgam of natural and managed plantations, including groves of Betula, Populus, and Ailanthus, and several other species of introduced, opportunistic or specialized plants that gradually claim managed, abandoned and even contaminated spaces. Here are the most notable examples of the park:

Bunker Gardens: A series of formal gardens in the image of medieval gardens flourishing in the galleries of the old coal ore bunkers. These gardens of remarkable variety, are linked by openings (mostly arched) cut into the concrete walls of the bunkers, they can also be contemplated from walkways overlooking the bunkers. In some cases, the soil composition of these gardens is contaminated by iron ore and coal deposits. While in other cases, the soil has been excavated and amended to reduce the level of toxic elements. These are contemplative gardens of a different kind; the techno-aesthetic embryo of terra-formation.

Cooling ponds: An integral part of an intelligent ecological system. These ponds serve as reservoirs for the retention of rainwater evacuated by an open sewer system linked to the adjacent buildings and surfaces. This process also serves to enrich the pond with oxygen, promoting the growth of plants that thrive in wetlands and creating a new type of biotope. 27

Cowper Square: Located at the foot of the impressive blast furnace structures in the central area of the park, the square features a tree plantation in a grid pattern, and serves as a place of contemplation and meeting. 28

Emscher Canal: The symbolic river of the park. The canal in this part of the site has been completely rehabilitated. Today, with the help of a hydrological system activated by a giant windmill (also an attraction of the park), the canal serves as a source of water supply for the gardens located on the upper levels of the site; moreover, this process contributes to the enrichment of the biological system. 29

Windmill - Emscher Canal (Water park)

27 - Kirkwood, p.154.

28 - Ibid.

29 - Ibid, p.155.

Conclusion

The Duisburg-Nord park project represents an experiment in the socio-cultural and aesthetic fields, envisaged on a grandiose landscape scale. Although one can cite antecedents in the genre of industrial parks (Industrio-parks), such as Richard Haag's project and the Gasworks Park in Seattle, it seems that the project envisaged by Latz & Partner is more complex on several levels, if we consider for example the problems associated with the decontamination and storage of toxic soils and other constraints due to the enormous size of the territory to be developed.

In addition, Duisburg-Nord is an attempt to rehabilitate a quasi-disaster site by holistic ecological means (e.g. rainwater capture, phyto-restoration measures, etc.) and an intelligent opportunistic and adaptive development strategy, but which also attempts to preserve the industrial remains that have marked this territory since the dawn of the industrial revolution. The goal is to make this site accessible to the community so that they can become aware of it and engage them to participate in the hope of protecting the industrial heritage and encouraging the effervescence and cultural diversity of the region. However, if we ignore the utopian vision and the romanticism associated with this park, we must first think about the question of public health. Would the presence of toxic materials on the site risk compromising the health of these users in the long term? Are we ready to accept living with the coexistence of toxic poisons in our parks?

Paradoxically, it goes without saying that the Duisburg-Nord park project arouses a great deal of interest, curiosity, and expectations, and therefore represents a model of exploration and research in the field of restoring disaster-stricken landscapes. Are we witnessing the genesis of a new landscape concept: the Laboratory Park?

Ore bunker gardens - Duisburg-Nord

Bibliography et Resources

Monographs

Bullock, A. et S. Trombley (revised edition 2000) The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern thought, London: Harper Collins.Hunt, J.D., 2000, Greater Perfections: the Practice of Garden Theory, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania press.Guédon, J-C , 1996, La planète cyber : Internet et cyberspace, Italie : Gallimard.Kirkwood, N., 2001, Manufactured Sites: Rethinking the Post-Industrial Landscape, New York: Spon Press.Weilacher, U., 1996, Between Landscape Architecture and Land-Art, Basel/Berlin/Boston: Birkhaüser.

Periodicals

Brandolini, S. (Nov. 2000) « Paradise Found », Architecture, v89, n11.Diedrich, L. (1999) A Renewal Concept for a Region, Callway/München*, No politics, no park: the Duisburg-nord model, Topos/European Landscape magazine, vol.26 (IBA, March).

Leppert, S. (Mar., 1998) Landschaftpark Duisburg-nord, Domus, n802.Steinglass, M. (Oct., 2000) The

Machine in the Garden, Metropolis, v20, n2.

Internet

- Official site of the firm of Latz & Partner

- Official site of the Duisburg-nord Parc (Landschaftpark Duisburg-nord)

- Image Galerie highlighting the Duisburg-nord Parc and its activities

Pierre Duranleau

Permaculture, Landscapes & Gardens: Designer, Consultant, Implementer & Practitioner

Pierre Duranleau - Copyright/Tous droits réservés - 2025